This paper explores how contextual factors shape the entrepreneurial identity in the start-up process. Through a single-case study, findings highlight how the industrial context, the team composition, and the growing sense of responsibility critically affect the nascent entrepreneur and his entrepreneurial identity from the pre-seed stage to the early stage.

Introduction

Throughout history, the concept of identity has engendered extensive scholarly discourse. Followers of Heraclitus articulated the doctrine of “Panta Rhei”, positing the perpetual flux and mutability of all entities, in stark contrast to the philosophical views of Parmenidean disciples. The latter defended the belief in the constancy of an object, asserting its persistence in preserving identical characteristics over time.

In the context of entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial identity (EI) is defined as the subjective and psychological representation of self as an entrepreneur (Gartner, 1988) and refers to the unique characteristics, values, beliefs, and behaviors that distinguish entrepreneurs from non-entrepreneurs. The identity perspective is considered a crucial lens to investigate entrepreneurship because it helps explain the diverse motivations driving entrepreneurs, including their distinct decision-making and strategic actions (Mmbaga et al., 2020). To this aim, several scholars have widely investigated this phenomenon to better predict entrepreneurial actions (McMullen and Shepherd, 2006) and to deeply understand the motivations behind the decision to run a successful business. However, the relationship between identity (self) and behavior is complex and probably reciprocal (Burke and Reitzes, 1981) and for these reasons, it can affect the venture creation in its whole process. In this vein, rather less attention has been paid to the contextual factors that affect EIs in the dynamic start-up process, both considering the reciprocal and mutual interplay of identity and behavior. Since EI can be considered context-specific and subject to interpretation based on culture, beliefs, and societal norms, assumptions about context can be challenged by new research findings. The ways contextual factors influence entrepreneurship is still an unexplored area in the literature despite its importance (Jones et al., 2019) and may have similar implications for the EI’s research stream.

In line with the studies of Parmenides and Heraclitus, this research seeks to explore whether and to what extent contextual factors shape EI in the start-up process. Specifically, the study aims to investigate whether an EI is embedded in a nascent entrepreneur since the beginning of the start-up process or if it is subject to significant changes influenced by contextual factors. Similarly, in the field of psychology, several scholars addressed the mutability of the identity positing its evolution over time. In this vein, identity change involves changes in the meaning of the self: changes in what it means to be who one is as a member of a group, who one is in a role, or who one is as a person. These meanings are held in the identity standard, the part of the identity that serves as a reference for judging self-in-situation meanings. Identities’ resistance to change gives them some stability; thus, change occurs only slowly in response to persistent pressure (Burke, 2006). Following the same logic, in the EI scenario, our research question is as follows.

Which contextual factors shape the entrepreneurial identity in the start-up process?

Literature Review

This work aims to bridge the massive bodies of materials related to the start-up process and EI’s literature to gain insights that can benefit both areas.

The creation of a venture is considered a challenging, complex, and often chaotic process determined by a set of iterative actions (Davidsson and Gordo, 2012). In this dynamic and iterative process, the foundational definition of a nascent entrepreneur comes to the forefront, a concept that has garnered widespread attention among various scholars. Simply put, a nascent entrepreneur is an individual actively involved in the establishment of a new business venture (Reynolds and White, 1997). This concept captures the essence of navigating the chaotic yet transformative landscape of entrepreneurship, where individuals embark on the journey of creating and shaping their ventures. This definition is crucial in our study because we are going to understand how contextual factors shape EIs in nascent entrepreneur since the literature is relatively scarce.

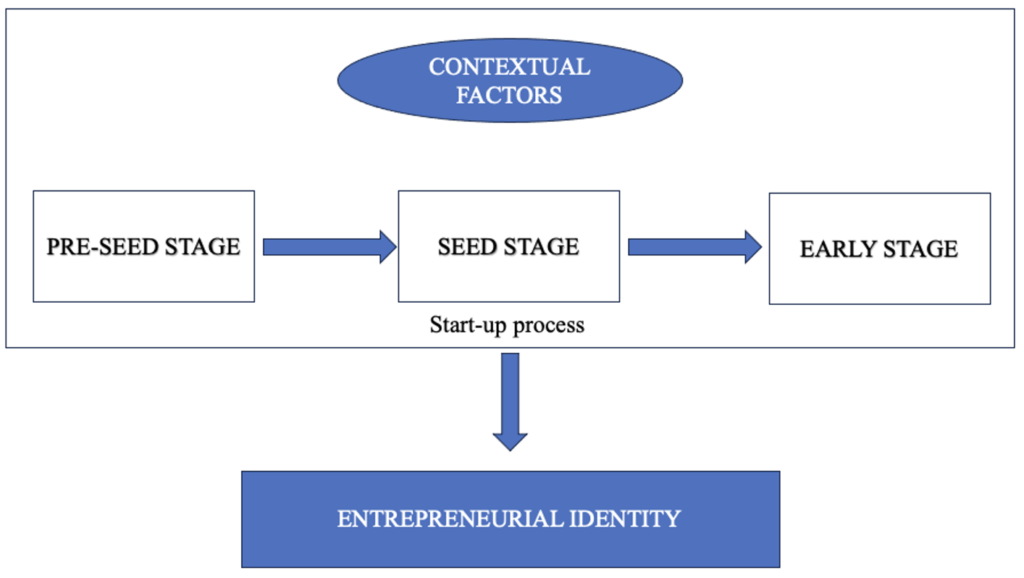

Conversely, relying on EI’s area, several scholars have investigated how the identity of entrepreneurs influences their behavior when engaged in new venture formation (Alsos et al., 2016). In this context, EI’s antecedents shape the way entrepreneurs deal with different tasks, especially in the early stages where start-up entrepreneurs spend significantly more time on environmental monitoring (Mueller et al., 2012). Relatedly Lichtenstein, et al., (2006), noted that start-up behaviors include investing personal capital, developing a prototype, defining an opportunity, organizing a founding team, forming a legal entity, purchasing major equipment, opening a bank account, and asking for funding. In this vein, contextual factors play a dual role: on one side, they act as antecedents of EI and may affect the early-growth stages. On the other side, new contextual factors, while the nascent entrepreneur embarks on the start-up journey, can shape his EI, and this is what this work aims to address (Fig.1). A desired identity to be an entrepreneur—as having potentially powerful effects on entrepreneurial activity, particularly at the start-up or gestational phase This seems to be consistent with Fauchart and Gruber (2011) who argued that entrepreneurs should be considered as carriers of an identity based on multiple sources combined according to context, situation, and stage of the firm’s life.

From a theoretical point of view, this paper will advance our understanding of EI dynamics in the start-up process. On the practical side, findings will be beneficial for nascent entrepreneurs embarking on the startup journey that may be influenced by similar contextual factors. Furthermore, this research can provide valuable insights for managers, empowering them to cultivate intrapreneurship by offering targeted support that may facilitate specific EI development and behaviors.

Methodology

The study employs a qualitative approach by presenting a single-case study according to Yin (2009). Lexmatic is an Italian start-up that was founded in July 2023. The founders created a legal software that utilizes augmented intelligence systems to automate the drafting of complex contracts. This technology instantly produces customized documents, enhancing the input provided by the user-lawyer. Apart from automating document drafting, communication, and email processes related to legal activities, the software offers additional functionalities. It facilitates instantaneous translation into foreign languages and provides digital assistance in locating doctrinal and jurisprudential contributions.

We decided to choose Lexmatic for three main reasons. First, the case can be considered a representative case study because the main founder is a nascent entrepreneur. Moreover, while developing Lexmatic, the founder is working in a big company as a lawyer. Indeed, the venturing efforts may occupy only part of the nascent entrepreneur’s time and use only part of his or her human and social capital (Dimov, 2010), so he perfectly assumes the characteristic of a nascent entrepreneur. Secondly, as artificial intelligence continues to advance, the obstacles encountered may hold substantial implications for the evolution of the start-up – that utilizes augmented intelligence systems – and potentially his EI. Third, as a newly established start-up, the entrepreneur should be equipped to articulate how contextual factors in recent months have reshaped his behaviors, potentially affecting his EI.

The units of analysis are the contextual factors that shape the EI in the start-up process.

In this case, semi-structured interviews were conducted with the main founder of the start-up, Tommaso. The dataset incorporates a set of two interviews of 2 hours, business records, and direct observations. The semi-structured interviews were focused on a wide range of topics, but they were mainly divided into two sections: 1) The development of the start-up from the pre-seed stage and 2) The perceived self-identity as an entrepreneur. The interviews were conducted in Italian, the interviewee’s native language, recorded and later fully transcribed. Afterward, they were translated into English. To enrich the general dataset of the paper, data triangulation was employed to better understand the phases of the start-up process: this technique involves the use of different sources of data to examine phenomena across settings and at different points in time (Denzin, 1970).

Finally, a content analysis was realized: this technique makes replicable and valid inferences from data to their context (Krippendorff, 1989). Both descriptive and interpretive encoding was performed using the software for qualitative analysis MAXQDA 11.

The findings are presented in the next section in a narrative form as an elaboration of Tab.1

Table 1 – Textual data

| Units of Analysis | Analytical Code | Textual data |

| Factors that shape the Entrepreneurial Identity in the start-up process | Industry | I think that was helpful for me to see friends of mine or parents who were enthusiastic about the idea, but I would say that the game changer was seeing my colleagues or people (more than friends or parents) who do my job, and I am not talking about the people who necessary work in my company. When the idea was more concrete, I saw in their eyes the potential usefulness of the project because in my friends I cannot see a real enthusiasm for a job-related thing such as this. My soul as an entrepreneur has changed from saying “I want to make small lawyers become big lawyers” therefore making a kind of “Robin Hood” in the legal field to “I realize that the sector of small-medium law offices” is not ready for this. I am currently working as a lawyer in a big company, and I felt that I needed to distinguish myself from the others. After the pre-seed phase, while developing the start-up, this need was even stronger. I feel like the start-up creation is building the way I need to distinguish myself even from other entrepreneurs to build something new, something different. |

| Growing sense of responsibility | For me at least as an entrepreneur, I am influenced by the fact that I have involved other people, so I am feeling a clear responsibility. And it is even more real for the money that was invested by people who are colleagues or friends of mine. From the pre-seed phase to the seed-phase I felt I had to generate concrete outcomes. I realized that this is the market and if the demand is not ready for that small segment of the market, I have to be a classic entrepreneur pursuing the goal of profit because I involved new people, it was not only about me. | |

| Team composition | The greatest shift in the way I am an entrepreneur today, happened thanks to the people in my team. I understood that it is not the spirit of the idea that is the key thing in running a successful business, but it is the execution capacity. When you see things from that perspective, so not from the perspective of the idea but from the perspective of the execution, it changes everything for you. In my specific situation, it changed in choosing a new target market. I started precisely with this friend of mine because you need someone to motivate you so that you can motivate each other. The change in my way of doing business happened when I made challenges with my team, not only in terms of the idea but also in the execution phase. I think that this was even stronger in the seed-phase where we had to concretely shape the way we wanted to generate income in the start-up, targeting a new segment. |

Industry

The narrative highlights a transformative moment triggered by the observation of colleagues’ reactions to the crystallization of the business idea. Unlike friends or parents, professional peers who are daily immersed in the same occupation provide a distinct lens through which the entrepreneur evaluates the viability and potential impact of the start-up. This emphasizes the role of the industry as a context (in terms of both professional networks and industry affiliations) and as an influential factor in shaping EI. The entrepreneur, in this case, perceives a more authentic and informed response from colleagues within the same professional domain, marking a shift in the conceptualization of the start-up’s potential.

The entrepreneur’s narrative emphasizes a substantial transition in his EI. Initially motivated by a desire to be a “Robin Hood”, seeking to empower smaller lawyers, a perceptible transformation occurs. The realization that market dynamics and demand ultimately dictate supply compels a shift towards a more conventional entrepreneurial pursuit focused on profitability. This attitudinal evolution is emblematic of the intricate interplay between personal personality traits, the environment, and the EI. It looks like there is a shift between two social identities described by Fauchart and Gruber (2011). In the first one, Tommaso’s social identity reflects the Communitarian, where the entrepreneur focuses on building a sense of community in his sector, providing a service that is welcoming and inclusive. In the second phase, there is a transition towards a Darwinian approach, with a notable change in his mindset. The primary motivation shifts from community building to a relentless pursuit of success in a competitive marketplace.

Furthermore, the entrepreneur’s professional context as a lawyer within a large corporate entity emerges as a salient contextual factor. The need for self-distinction within this professional setting becomes a catalyst for EI. As the start-up progresses beyond the pre-seed phase, this need intensifies, indicating that the EI is not only shaped by external stimuli but also by an internal quest for differentiation within the professional landscape. To this aim, it is clear that context is an important contributor to EI, as it provides the social cues that influence the individual’s sense of belonging and/or differentiation from their social groups (Donnellon et al., 2014)

Growing sense of responsibility

Central to this evolution is the entrepreneur’s sense of responsibility, a crucial factor conditioned by the involvement of external stakeholders and financial investments. The sense of responsibility grows when the investors are colleagues or friends, adding a layer of personal connection and accountability to the entrepreneurial endeavor. For these reasons, in this work, the sense of responsibility is contextual because it grows when the start-up meets new difficulties and when new investors join the company. The transition from the pre-seed to the seed phase accentuates the tangible pressure felt by the entrepreneur to generate concrete outcomes. The weight of trust and expectations of those who have invested, both emotionally and financially, contribute significantly to the shaping of the EI. The growing sense of responsibility can also be seen as a contextual factor that shape the transition of his EI. Initially motivated by a desire to empower smaller lawyers and effectuate a form of “legalistic Robin Hoodism”. The entrepreneur’s realization that market demand dictates supply precipitates a shift toward a more conventional profit-driven entrepreneurial orientation. This shift captures the impact of market dynamics on shaping the entrepreneur’s goals, but also the fact that he has involved other people, and he needs to provide concrete solutions.

Team composition

The shift in how the entrepreneur sees his work, as shared in the story, is shaped by key aspects of starting a business. Moving from the pre-seed stage to the early stage has reshaped how entrepreneurs approach their goals, but also the way he is influenced by the team composition, and the various stakeholders. To this aim, the importance of working together with a team stands out. The story highlights how the people you work with can profoundly impact your understanding of the business but also the way team collaboration, illustrated through a supportive friend and challenges faced together, plays a crucial role in shaping how entrepreneurs see themselves. This seems to be consistent with Falck et al., (2012) who argue that an individual’s entrepreneurial identity is shaped by an individual’s parents and peer group. This collaborative process becomes particularly important during the seed phase, a critical time when a start-up needs to figure out “how to make money” and convince investors to join the project. In this vein, the team composition is a contextual factors that seem to evolve with the EI, because of the specific situational factors of each start-up phase, but also for the new contextual needs, opportunities, and constraints that different actors experience in the team.

Discussions and conclusions

This research work contributes to the field of EI on both a theoretical and practical level.

First, this research advances our understanding of the influence of contextual factors on EIs. Second, it emphasizes the importance of examining the EI phenomena during the entire start-up process. Each start-up stage can be seen as a new world where the entrepreneurs face new challenges. Contextual factors seem to play a crucial role in shaping EIs, especially for nascent entrepreneurs. Third, it will serve as a basis to supply and motivate other studies and research in complementary fields, where my findings may be useful to address the nature of the link between the context and entrepreneurial intentions. Furthermore, through this work, the nascent entrepreneurs will concretely experience a real-case start-up story, identifying commonalities and opportunities to deal with situational and contextual factors that may affect their EIs and consequently, their start-up behavior.

Several limitations exist in the research. First, the findings are limited to nascent entrepreneurs. Second, given the exploratory character of the study, the author’s data collection and interpretation may be vulnerable to criticism and prejudice. Third, the study has not employed a longitudinal study and we cannot easily assume when the EI has changed.

Future research can 1) conduct a multiple-case study to better understand the contextual factors shaping the EI, even considering non-nascent entrepreneurs 2) focus on a quantitative study using a bigger number of data and a larger sample 3) employ a longitudinal study to better freeze the EI’s change in different start-up phases, to respond to new research questions.

Parmenides or Heraclitus?

References

Alsos, G. A., Clausen, T. H., Hytti, U., & Solvoll, S. (2016). Entrepreneurs’ social identity and the preference of causal and effectual behaviours in start-up processes. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 28(3-4), 234-258.

Burke, P. J. (2006). Identity change. Social psychology quarterly, 69(1), 81-96.

Burke, P. J., & Reitzes, D. C. (1981). The link between identity and role performance. Social psychology quarterly, 83-92.

Davidsson, P., and S. R. Gordon. (2012). “Panel Studies of New Venture Creation: A Methods-Focused Review and Suggestions for Future Research.” Small Business Economics 39 (4): 853–876. doi: 10.1007/s11187-011-9325-8

Dimov, D. (2010). Nascent entrepreneurs and venture emergence: Opportunity confidence, human capital, and early planning. Journal of management studies, 47(6), 1123-1153.

Donnellon, A., Ollila, S., & Middleton, K. W. (2014). Constructing entrepreneurial identity in entrepreneurship education. The International Journal of Management Education, 12(3), 490-499.

Falck, O., Heblich, S., & Luedemann, E. (2012). Identity and entrepreneurship: do school peers shape entrepreneurial intentions?. Small Business Economics, 39, 39-59.

Farmer, S. M., Yao, X., & Kung–Mcintyre, K. (2011). The behavioral impact of entrepreneur identity aspiration and prior entrepreneurial experience. Entrepreneurship Theory and practice, 35(2), 245-273.

Fauchart, E., & Gruber, M. (2011). Darwinians, communitarians, and missionaries: The role of founder identity in entrepreneurship. Academy of management journal, 54(5), 935-957.

Hoang, H., & Gimeno, J. (2010). Becoming a founder: How founder role identity affects entrepreneurial transitions and persistence in founding. Journal of business venturing, 25(1), 41-53.

Jones, P., Ratten, V., Klapper, R., & Fayolle, A. (2019). Entrepreneurial identity and context: Current trends and an agenda for future research. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 20(1), 3-7.

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage publications.

Learned, K. E. (1992). What happened before the organization? A model of organization formation. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 17(1), 39-48.

Lichtenstein, B., Dooley, K., & Lumpkin, G. (2006). Measuring emergence in the dynamics of new venture creation. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(2), 153–175.

Mathias, B. D., & Williams, D. W. (2017). The impact of role identities on entrepreneurs’ evaluation and selection of opportunities. Journal of Management, 43(3), 892-918.

McMullen, J. S., & Shepherd, D. A. (2006). Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Academy of Management review, 31(1), 132-152.

Mmbaga, N. A., Mathias, B. D., Williams, D. W., & Cardon, M. S. (2020). A review of and future agenda for research on identity in entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 35(6), 106049.

Mueller, S., Volery, T., & Von Siemens, B. (2012). What do entrepreneurs actually do? An observational study of entrepreneurs’ everyday behavior in the start–up and growth stages. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(5), 995-1017.

Murnieks, C., & Mosakowski, E. (2007). Who am I? looking inside the’entrepreneurial identity’. Frontiers of entrepreneurship research.

Obschonka, M., Silbereisen, R. K., Cantner, U., & Goethner, M. (2015). Entrepreneurial self-identity: predictors and effects within the theory of planned behavior framework. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30, 773-794.

Pittino, D., Visintin, F., & Lauto, G. (2017). A configurational analysis of the antecedents of entrepreneurial orientation. European Management Journal, 35(2), 224-237.

Powell, E. E., & Baker, T. (2014). It’s what you make of it: Founder identity and enacting strategic responses to adversity. Academy of Management Journal, 57(5), 1406-1433.

Prochotta, A., Berger, E. S., & Kuckertz, A. (2022). Aiming for legitimacy but perpetuating clichés–Social evaluations of the entrepreneurial identity. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 34(9-10), 807-827

Radu-Lefebvre, M., Lefebvre, V., Crosina, E., & Hytti, U. (2021). Entrepreneurial identity: A review and research agenda. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(6), 1550-1590.

Shepherd, D., & Haynie, J. M. (2009). Birds of a feather don’t always flock together: Identity management in entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(4), 316-337.

Stets, J. E., Burke, P. J., Serpe, R. T., & Stryker, R. (2020). Getting identity theory (IT) right. In Advances in group processes (Vol. 37, pp. 191-212). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Wagenschwanz, A. M. (2021). The identity of entrepreneurs: Providing conceptual clarity and future directions. International Journal of Management Reviews, 23(1), 64-84. Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (Vol. 5). sage.

Autori

Università degli Studi di Roma “Sapienza”